Two angles on why we need the nation state

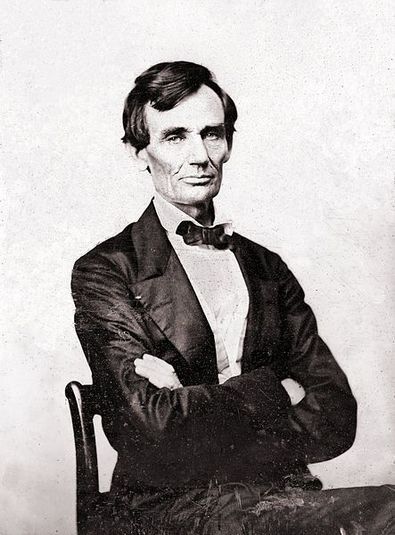

The two angles are from the English conservative writer and philosopher Roger Scruton, and from the economist Dani Rodrik, who, outside his technical economic writings, appears to be a conventional American liberal – horrified by Trump and so forth. Yet both, in sometimes overlapping, sometimes complementary ways, make a persuasive case on the need for strong nation states in an age of globalization. At the cost of making this post much too long, I cite Abraham Lincoln as the exemplar of a political leader who had long ago mastered some main insights of Scruton and Rodrik.

The two angles are from the English conservative writer and philosopher Roger Scruton, and from the economist Dani Rodrik, who, outside his technical economic writings, appears to be a conventional American liberal – horrified by Trump and so forth. Yet both, in sometimes overlapping, sometimes complementary ways, make a persuasive case on the need for strong nation states in an age of globalization. At the cost of making this post much too long, I cite Abraham Lincoln as the exemplar of a political leader who had long ago mastered some main insights of Scruton and Rodrik.

Roger Scruton: the place that is ours

In a WSJ essay ‘The Case for Nations’, Scruton observes “a respectable opinion among educated people” that the nation state has been outmoded by globalization and the internet, which have created “new networks of belonging and new forms of social trust, by which borders are erased and old attachments vaporized.”

This “respectable opinion” is questionable because “democratic politics requires a demos. Democracy means rule by the people and requires us to know who the people are, what unites them and how they can form a government. Government in turn requires a ‘we,’ a prepolitical loyalty that causes neighbors who voted in opposing ways to treat each other as fellow citizens, for whom the government is not ‘mine’ or ‘yours’ but ‘ours,’ whether or not we approve of it.”

So, Scruton’s argument is that if we care about liberal democracy, then the existence of a prepolitical loyalty or sense of ‘we’ is a necessary condition for its existence. It is necessary but not sufficient, however, because not every kind of loyalty provides a favorable ground for liberal democracy.

Religion is one sort of loyalty that is (usually) both transnational and, especially in its untamed primal spirit, not especially tolerant of difference, dissent or competition. “In the world as it is today”, says Scruton, “the principal threat to national identity remains religion, and in particular Islam, which offers to its most ardent subscribers a complete way of life, based on submission to the will of God”, while it was not too long ago that militantly opposed Christianities ravaged Europe in the Wars of Religion of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Or take those urban elites most directly tied in to globalization, who, ‘like the aristocrats of old’, form networks and loyalties without reference to national boundaries. These elites nevertheless still depend on others – factory workers, nurses, cleaners, police, soldiers and many others – who do not belong to the transnational elite, and who can seriously inconvenience it at times - by voting for ‘Brexit’, say. Although Scruton does not spell out the implication, one can imagine that these elites might lose interest in democracy, in favor of top-down rule by unelected but expert international administrators, like the European Commission, say.

Distinct from religion or business globalism, it is national loyalty that is the most reliable support for liberal democracy. Scruton is especially enlightening on the importance of geography, territory or place – the sheer love of home.

“National loyalty marginalizes loyalties of family, tribe and faith, and places before the citizens’ eyes, as the focus of their patriotic feeling, not a person or a religion but a place. This place is defined by the history, culture and law through which we, the people, have claimed it as our own. The nationalist art and literature of the 19th century is characterized by the emergence of territory from behind religion, tribe and dynasty as the primary objects of love … It is our home that we fight for, and our freedom is the freedom of self-government in the place that is ours. … When we wish to summon the “we” of political identity … We refer simply to the country, this spot of earth, which belongs to us because we belong to it, have loved it, lived in it, defended it and established peace and prosperity within its borders.”

National loyalty is the best foundation for liberal democracy because it is the most inclusive foundation:

“On the foundation of national attachment it has been possible to build a kind of civic patriotism, which acknowledges institutions and laws as shared possessions and which can extend a welcome to those who have entered the social contract from outside. You cannot immigrate into a tribe, a family or a faith, but you can immigrate into a country, provided you are prepared to obey the rules that make that country into a home. … The “clash of civilizations,” which, according to the late political scientist Samuel Huntington, is the successor to the Cold War is, in my view, no such thing. It is a conflict between two forms of membership—the national, which tolerates difference, and the religious, which does not. It is this toleration of difference that opens the way to democracy.”

Dani Rodrik: a principled (economic) defense of the nation state

In his Aeon magazine essay ‘Why Nation States are Good’ – what editor thought up this clunky title? – Dani Rodrik starts from the same place as Scruton, “ the deep rift that has opened between the worldview of the global intellectual and professional elites, and that of ordinary citizens”, driven by “elites’ attachment to a globalist mindset that underplays and weakens the nation-state”. This is a mindset that threatens not only economic prosperity but also the liberal democratic order, which might be swept away by the backlash against its blind spots and excesses.

Historically, the nation state “has curbed internecine violence, expanded networks of solidarity beyond the local, spurred mass markets and industrialisation, enabled the mobilisation of human and financial resources, and fostered the spread of representative political institutions”. Looking forward, “The globalist worldview is grounded in the argument that an interconnected world economy requires collective action at the global level. But this premise is largely false.”

The first step in Rodrik’s ‘principled defense of the nation-state’ is the proposition that markets require rules. “Markets are not self-creating, self-regulating, self-stabilising or self-legitimising, so they depend on non-market institutions. … Behind every functioning, sustainable market stands a wide range of institutions providing critical functions of regulation, redistribution, monetary and fiscal stability, and conflict management.”

The second step is to note that these institutional functions have so far been provided largely by the nation-state. During the Bretton Woods system of international cooperation from the 1950s to the 1970s, and even beyond, countries maintained a wide latitude in managing their own economies and social contracts, and yet "the postwar years saw historic growth in trade and investment, in no small part because Bretton Woods encouraged healthy domestic policy environments.”

The third point is that there are, in fact, no authoritative transnational rule-making institutions to replace the nation state, and, more importantly, that it would be counter-productive to try to do so. There simply is no single set of ‘best practice’ market-supporting institutions that would be optimal for the world as a whole. Advanced nations – the United States, Japan, individual European nations – have developed under quite different institutional setups for corporate governance, labor markets, finance, and so on, and yet have reached comparable levels of wealth. “Yes, markets, incentives, property rights, stability and predictability are important. But they do not imply unique blueprints.” Not only that, but “there is no reason to think that the range of institutional divergence we observe in the world today exhausts all feasible possibilities. Desired institutional functions…can be generated in many different ways. The only limit is set by our imagination.”

Fourth, “Given the non-uniqueness of practices and institutions enabling capitalism, it’s not surprising that nation-states also resolve key social trade-offs differently. The world does not agree on how to balance equality against opportunity, economic security against innovation, health and environmental risks against technological innovation, stability against dynamism, economic outcomes against social and cultural values, and many other consequences of institutional choice. Developing nations have different institutional requirements than rich nations. There are, in short, strong arguments against global institutional harmonisation.”

Lastly, “a divided global polity presents an additional advantage. It enables experimentation, competition among institutional forms, and learning from others. To be sure, trial and error can be costly when it comes to society’s rules. Still, institutional diversity among nations is as close as we can expect to a laboratory for capitalism in real life.”

“Insufficient appreciation of the value of nation-states”, Rodrik concludes, “leads to dead ends. We push markets beyond what their governance can support; or we set global rules that defy the underlying diversity of needs and preferences. We eviscerate the nation-state without compensating improvements in governance elsewhere. The failure to grasp that nation-states constitute the foundation of the capitalist order lies at the heart of both globalisation’s unaddressed iniquities, as well as the decline in the health of our democracies.”

Lincoln: “the electric cord… that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men”

Although it will make this post much too long, I cannot resist quoting Abraham Lincoln, who had much of this worked out long ago. In his speech of July 10, 1858, during the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln spoke on the meaning of July 4, American Independence Day:

“We run our memory back over the pages of history for about eighty-two years … We find a race of men living in that day whom we claim as our fathers and grandfathers; they were iron men, they fought for the principle that they were contending for; and we understood that by what they then did it has followed that the degree of prosperity that we now enjoy has come to us. We hold this annual celebration to remind ourselves of all the good done in this process of time of how it was done and who did it, and how we are historically connected with it; and we go from these meetings in better humor with ourselves—we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit. In every way we are better men in the age, and race, and country in which we live for these celebrations.

“But after we have done all this we have not yet reached the whole. There is something else connected with it. We have besides these men—descended by blood from our ancestors—among us perhaps half our people who are not descendants at all of these men, they are men who have come from Europe—German, Irish, French and Scandinavian—men that have come from Europe themselves, or whose ancestors have come hither and settled here, finding themselves our equals in all things. If they look back through this history to trace their connection with those days by blood, they find they have none, they cannot carry themselves back into that glorious epoch and make themselves feel that they are part of us, but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find that those old men say that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration [loud and long continued applause], and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world. [Applause.]”

Perhaps half of the population were not descendants at all by blood of the ‘iron men’ who made the Revolution. Yet all could unite in patriotic love of their common home – “we feel more attached the one to the other, and more firmly bound to the country we inhabit” – and of the ideals and principles animating that country's republican form of government.

As to an important role for the nation state in promoting capitalist economic development, this was, along with its stand on slavery, one of the main planks differentiating the Republican party of Lincoln’s day from the Democrats and the laissez-faire Southern plantocracy. But that’s too big and important a subject to tack on to this already overlong post.